In 1968 a definition of the concept of hyperactivity was incorporated in the official diagnostic nomenclature, the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II). The term used to label children at that time was “Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood.” In 1980 almost 5 years after special education was signed into law the DSM-III took the position that hyperactivity was no longer an essential diagnostic criterion for the disorder and thus the term “Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) came to be. Finally in 1987 the term was renamed to “Attention deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

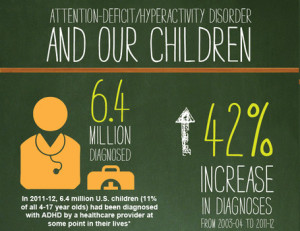

Today the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 5% of children in the United States have ADHD. That means that roughly 2.7 million children in grades k-12 have a diagnosis of ADHD in the United States. It is known that 11.5% of all k-12 students receive special education nationally. In 2004 the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) reported that 37% of the special education population had ADHD. In other words, over a third of the children who receive special education ten years ago had ADHD. How are these children being supported educationally?

In reviewing the literature on educational research and governmental guidelines and recommendations there continues to be an absence of the “teaching of skills” to children with ADHD. In every corner of the literature there are plenty of examples of how to “accommodate” the child with ADHD, but very little in the way of remediation of executive skills. Still much of the research points to the direction of medication for children with ADHD. There have been attempts at instructional methods for supporting children with ADHD.

It’s well known in education that children with ADHD tend to experience the greatest challenges as they get closer to middle school. During this time the expectation shifts from the adult management of the child to the child increasing self-management. Different from first grade when teachers could “pin” notes on the backpacks and stuff packets into weekly folders, the student is expected to take over the management of learning. This is when children with ADHD fall apart. In middle and high schools today the best treatment for children with ADHD continues to be the only classroom on the campus where there is no required curriculum. It is the class that is the least monitored and supported by administrators. It is the classroom that kids go to for up to 5 hours a week to get help. This is the “study skills” class. It’s the class that every parent hopes will be the answer to their prayers. It’s the class that educators declare will solve all the problems. In some cases this 5-hour a week treatment for children with ADHD makes a difference because it allows students more time to complete assignments and homework.

However, in most cases teachers are left to figure out for themselves what and how to teach the students who forget, loose track, and can’t find

Often the class ends up being a study hall where children with ADHD continue to get more time to practice bad habits and continue to demonstrate their unfortunate dependence on an adult prompting them to “do their work.” Since there is not a mandate on curriculum or even guidelines at the state or local level the class continues to go unsupported. Today there are plenty of evidence-based, neuroscience supported programs and curriculum for children with ADHD. These programs must be brought into the study skills classes for children with ADHD and executive function deficits. Children need to learn, practice, and receive reinforcement for using the executive function skills. The acquisition of these skills should be a primary focus in secondary school. Instead of the focus of a Grade Point Average (GPA), the child with ADHD should be rewarded for learning how to navigate learning with greater independence.

As special education approaches its 40th birthday, there is much to celebrate. However, for children with ADHD in public schools there’s still much work to be done. Today children with ADHD are still misunderstood and not completely educated. The skills they lack can be accommodated for within the current system, however when they leave the public school system and go out on their own many of these young adults experience failure. The question remains, are children with ADHD leaving public schools with “tools” and “skills” that they can use independently for life? Here are my recommendations for tools and curriculum to help support the life long journey:

Demand evidence based Interventions and Treatments for students with ADHD.

This curriculum is for school from K-12. It’s systematic and there are many great details for educators to incorporation.

http://premier.us/tools-planning/products-students/programs-workshops/executive-functions-skill-building-program

Executive Functions Training Elementary:

https://www.linguisystems.com/products/product/display?itemid=10697

Working Memory: chunking and rehearsing, linking and associations, acronyms and silly sentences, paraphrasing, and visualizing

Time Management: estimating time, planning for homework and long-term assignments, studying for tests

Planning & Organization: brainstorming, organizing notes and information, reading with a purpose, writing efficiently

Flexible Thinking: reorder sentence, rewrite sentences and paragraphs, homographs, intonation and stress

Self-Monitoring: checking for mistakes, editing written work, identifying key words in directions, combining information

Skills for Behavior–Doing: strategies for inhibition, emotional control, attention, and initiation

Much more than activities, this resource gives clinicians tools to measure and establish executive function skills. Each skill area contains:

- detailed teaching instructions

- activities organized into sub-skills

- exercises for varying ability levels

- goals

- teaching strategies

- a section review with guidelines for skill mastery

- extension activities

- parent strategies

- teacher strategies